This article by James Hughes (Technical Director: Climate and Resilience) and Simon Harvey (Specialist Sustainability Services Advisor) at Tonkin + Taylor New Zealand explores the legislative framework, current state of climate risks, impacts already observed, and the role of consultants and engineers in navigating this evolving landscape.

The context for this article also needs to take account of recent anomalies in global temperature trends, which have raised concerns among climate scientists. The unexpected acceleration in sea surface temperatures underscores the urgency of robust climate action. Such uncertainties challenge traditional risk management approaches and emphasise the need for adaptive strategies in infrastructure planning and development.

What’s the legislative framework and policy landscape?

Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019

Central to New Zealand’s climate action is the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019. This legislation establishes a comprehensive framework by which New Zealand can develop and implement clear and stable climate change policies. Key provisions include:

- Creation of the Climate Change Commission to advise on emissions budgets and adaptation plans

- Implementation of emissions reduction targets and budgets to reduce net emission of all greenhouse gases (except biogenic methane) to zero by 2050

- Requiring the Government to develop and implement policies for climate change adaptation (including a National Climate Change Risk Assessment and a National Adaptation Plan)

- Mandating regular government reporting to track progress towards climate goals

Current initiatives and strategic context

National Climate Change Risk Assessment (NCCRA)

The National Climate Change Risk Assessment, conducted every six years, identifies 43 priority risks across various domains. These risks include threats to potable water supplies, impacts on indigenous ecosystems, and economic costs from extreme weather events and sea-level rise.

First National Adaptation Plan

Published in 2024, the National Adaptation Plan outlines strategies to integrate climate resilience into governance, community planning, and business operations. It emphasises equitable transition and collaboration among government sectors, local councils, Māori communities, and private enterprises.

Climate Change Commission (He Pou a Rangi)

The Climate Change Commission provides independent advice on emissions budgets and policy effectiveness. Its role includes periodic reviews of emission targets and advising on adjustments to meet climate commitments.

Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP #2)

The country’s second Emissions Reduction Plan, currently under consultation, focuses on market mechanisms and private sector involvement to achieve emission reduction targets. Key policies include increasing renewable energy, providing public EV chargers, lowering agricultural emissions, investing in resource recovery, improving public transport, and exploring carbon capture technologies.

Mandatory climate reporting

Under the Financial Sector (Climate-related Disclosures and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2021, Climate Reporting Entities must disclose climate-related financial impacts. This framework aims to enhance transparency and accountability among large organisations and the financial sector.

Climate strategy and policy development

New Zealand’s five-point climate strategy, unveiled in July 2024, outlines five key pillars:

- Infrastructure is resilient and communities are well prepared

- Credible markets support the climate transition

- Clean energy is abundant and affordable

- World-leading climate innovation boosts the economy

- Nature-based solutions address climate change.

The strategy emphasises the importance of private investment and partnerships, access to data and evidence, international engagement and knowledge sharing, and competitive markets.

Legislative review for climate event recovery

The Severe Weather Emergency Legislation Act, passed in March 2023, amends several laws, including the Resource Management Act (RMA). The changes aim to provide more time for notifying councils and applying for consents for emergency work and adjust notice requirements for councils exercising emergency powers under the RMA.

National Policy Statement (NPS) on natural hazard decision-making

The NPS will guide local authorities on natural hazard risk considerations in policy and planning. It aims to limit new building in high-risk areas and require risk reduction actions in moderately risky areas.

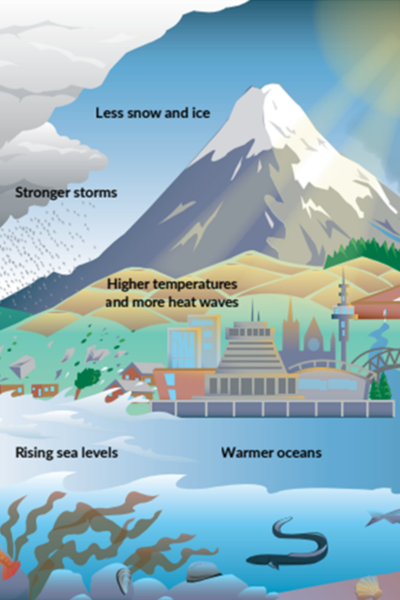

What are the climate risks and vulnerabilities in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Based on the NCCRA and other reports, priority climate risks for New Zealand include:

Based on the NCCRA and other reports, priority climate risks for New Zealand include:

- Water supply security: Vulnerabilities in availability and quality of potable water due to changes in rainfall, temperature, drought, extreme weather events and ongoing sea-level rise

- Economic impacts: Government costs associated with lost productivity, disaster relief expenditure and unfunded contingent liabilities due to extreme events and ongoing, gradual changes

- The built environment: Risks to buildings due to extreme weather events, drought, increased fire weather and ongoing sea-level rise.

- Biodiversity loss: Threats to indigenous ecosystems and species from the enhanced spread, survival and establishment of invasive species due to climatic change

- Coastal ecosystems: Threats to intertidal zones, estuaries, dunes, coastal lakes and wetlands, due to ongoing sea-level rise and extreme weather events

- Community disparities: Differential impacts on vulnerable populations, including Māori communities, requiring tailored adaptation strategies.

Māori likely to be disproportionately affected

The NCCRA report identifies that Māori, New Zealand’s indigenous population, are likely to be disproportionately affected by the priority risks. Some iwi (tribes) support the need for a parallel risk assessment carried out by Māori for Māori. And some iwi and hapu (sub-tribes) are already developing their own climate change plans.

Risks of particular significance to Māori include:

- Risks to social, cultural, spiritual and economic wellbeing from loss and degradation of lands and waters; and from loss of taonga (treasured) species and biodiversity

- Risks to social cohesion and community wellbeing from displacement of individuals, families and communities

- Risks of exacerbating and creating inequities due to unequal impacts of climate change

Vulnerable infrastructure

Research by Tonkin + Taylor commissioned by Local Government New Zealand assessed the vulnerability of local government infrastructure in New Zealand to sea level rise, highlighting critical findings and recommendations. The study focused on quantifying the exposure of infrastructure, including roads, water systems, buildings, greenspaces, jetties, and airports, at various sea level increments – 0.5m, 1.0m, 1.5m, and 3.0m above mean high water springs (MHWS). It revealed that approximately $5 billion worth of council-owned infrastructure is currently at risk up to 1 meter above MHWS, escalating to around $14 billion at 3 meters.

Beyond quantifying risks, the report emphasises the need for co-ordinated responses to rising sea levels. Specific recommendations include improving intra-council co-ordination across finance, geospatial information, and asset management. It also stresses the importance of inter-council collaboration for long-term planning and resource management, as well as enhanced co-operation between central and local governments to address climate change challenges collectively.

Economic dependence and transition risks

New Zealand’s economy heavily relies on agriculture, forestry, and tourism, which are vulnerable to both physical and transition climate change impacts. Agriculture, particularly dairy, accounts for over half of the country’s emissions. Dairy, red meat, and tourism sectors also face risks as global preferences and regulations shift towards lower-emission products. Despite agriculture being exempt from the Emissions Trading Scheme to maintain global competitiveness, the government plans to invest $400 million in reducing on-farm emissions. This shift poses challenges to New Zealand’s reputation as a producer of environmentally friendly goods, impacting market access and international standing with customers and markets favoring low-emission products.

What impact is climate change already having in New Zealand?

Many anticipated climate risks are already playing out across communities and sectors within New Zealand.

The recent report Our Atmosphere and Climate 2023 details climate change impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems. It highlights direct effects on species and ecosystems, impacting public health, culture, economy, and recreation. High level changes include habitat shifts, species decline, and altered ecosystem dynamics due to rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events. The report also highlights the need to understand the impacts of climate change through a te ao Māori (the Māori world) and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) perspective.

Specific impacts in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Temperature and frost days: Long-term temperature rise and declining frost days are reshaping agricultural suitability, affecting crops like kiwifruit and wine. This impacts Māori customary practices and increases invasive pest risks.

- Rainfall patterns: Southern regions are becoming wetter, while northern and eastern areas experience drying trends, affecting stormwater infrastructure and increasing flood risks.

- Extreme weather events: Intense events like atmospheric rivers and cyclones are more frequent, causing substantial damage and the largest insurance losses since the Canterbury earthquakes.

- Sea level and ocean changes: Rising sea levels, warming oceans, and acidification are diminishing habitat availability and affecting marine species like shorebirds and kelp.

- Ecosystem cascading effects: Climate impacts compound threats from invasive species and human disturbances, affecting biodiversity and ecosystem resilience.

All of these impacts come with associated and consequential economic costs. An example is the extreme weather events in January and February 2023 with insurance industry cost of approximately. $3.8b combined. This is the largest financial event for the insurers since the devastating Canterbury earthquakes in 2011.

As a consequence of these financial impacts, insurers are increasingly moving towards risk-based pricing models, which increase insurance costs for areas more exposed to climate change impacts. Insurers are also withdrawing from providing cover to higher-risk, flood prone areas which further reduces community resilience and recovery opportunities.

What are the current challenges for consultants and engineers?

Uncertainty and regulatory complexity

Consultants face challenges in navigating regulatory frameworks that are evolving in response to emerging climate impacts. Short-term political cycles and varying local council approaches further complicate long-term planning and infrastructure development.

Client expectations and financial constraints

Clients increasingly demand innovative solutions that balance climate resilience with economic viability. Designing resilient infrastructure requires addressing uncertainty about future climate scenarios and integrating adaptive management strategies.

Skills and expertise

Consultants must cultivate expertise in climate science, risk assessment, and sustainable design practices. Embracing systems thinking and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration are essential to developing holistic solutions that meet diverse client needs.

How might environmental and engineering consultants respond to the opportunities and responsibilities of addressing climate change?

To respond to the unprecedented climate change and sustainability challenges, consultants must ensure future-fit solutions that address systemic degradation of natural and social capital. This requires broad and profound changes in how we plan our built environments and, more fundamentally, how we see our relationship with the natural world. In this context, specific challenges and opportunities for consultants include:

- Providing services which address dynamic and complex issues like biodiversity loss, circular economy, and just transition in meaningful ways as part of every project.

- Staying updated with emerging (and fast changing) science relating to climate change and other sustainability challenges; and building appropriate knowledge, capacity and service offerings to address these in the local context. For example, in Aotearoa New Zealand, adopting a partnership approach with local iwi and hapu, as well as the wider community, is vital.

- Encouraging clients to adopt inclusive, just, and environmentally restorative solutions. A local example is the restoration of the Kopurererua Valley wetland as part of a cycle path development.

- Developing new services for genuinely sustainable outcomes through radical collaboration across sectors and disciplines. This includes engaging with communities and public sector agencies in participatory democracy processes. A recent example is the deliberative democracy approach to developing a congestion charging regime for Auckland.

- Taking a systems approach to problems, better recognising trade-offs and cascading implications, and trying, wherever possible, to take a multi-generational, long-term perspective (drawing on indigenous Māori knowledge). A recent example of this approach is the Clifton to Tangoio Adaptation Strategy.

Conclusion

Climate change is happening faster than models predict, exacerbating issues like biodiversity loss and social inequity. The window to mitigate the consequential financial, social, and environmental costs is closing rapidly, making the need for more effective responses increasingly urgent.

Globally, the transition to low-carbon energy sources is gathering pace, though being offset by continued use and expansion of fossil fuels. There is a growing awareness that the challenges and solutions require not only technological changes, but societal, behavioral, and arguably deeper systemic shifts.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the impacts are already being felt through recent extreme events around the country – affecting thousands of people, and imposing huge economic costs. The impacts are uniquely experienced by Māori communities, threatening their wellbeing, cultural values and practices, as well as their primary sector economic interests. At the same time, working in partnership with Māori offers valuable perspectives for a more holistic view of our relationship with the natural world.

Given the complex issues and context to work within, environmental and engineering consultants must step up to these augmenting responsibilities. They must deliver environmentally restorative solutions and services that achieve genuinely sustainable outcomes. Engaging in meaningful dialogue with communities and the public sector is essential. Consultants should also consider new ways of thinking and designing to address climate change and other sustainability challenges.

This article first appeared in ASPAC News, the quarterly newsletter of FIDIC Asia Pacific.